MMIM Hall of Fame

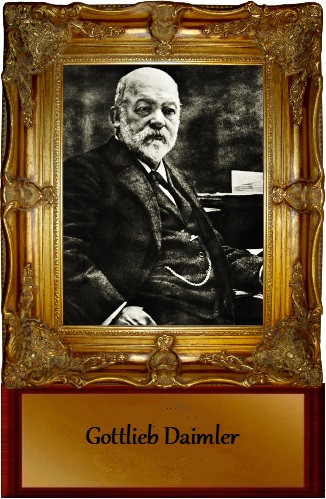

Gottlieb Daimler

Entrepreneur, industrialist, engineer, Inventor and prodigious innovator, Gottlieb Daimler’s pioneering work on internal-combustion engine designs gave Europe a light, compact, high-speed gasoline engine which could be used to power automotive vehicles, boats and, well, almost anything else.

Gottlieb Wilhelm Daimler’s abilities as a businessman also led to the founding of Daimler AG, now the world’s oldest automotive manufacturer still in production. Daimler was, without doubt, a most distinguished German engineer holding an important place amongst the founding fathers of the automobile industry.

Gottlieb Wilhelm Daimler was Born on the 17th of March, 1834, in a small town of less than 4,000 souls called Schorndorf, Rems-Murr-Kreis, approx' 20km East of Stuttgart, in the Kingdom of Württemberg (a federal state of the German Confederation), in what is now Southwest Germany.

Gottlieb Wilhelm Daimler’s father was Johannes Däumler (also recorded as Deumler or Teimbler), was born on the 21st of December 1801, a master baker and innkeeper who lived his whole life in Schorndorf. The Daimlers had been master bakers for generations having lived in the area for over 200 years. The Daimler bakery at 7, “Höllgasse” or “Helle Gasse” (“light alley”), in the picturesque town of Schorndorf, above which Gottlieb was born, is a timber framed building purchased by Gottlieb's grandfather through two instalments in 1787 and 1806. Johannes Daimler had inherited it in 1825 and the young Gottlieb, his elder brother Johannes, b1832, and younger brothers Karl Wilhelm, b1840, and Christian Albert, b1845, all grew and attended the local school from this home. Gottlieb was still at home here during his apprentice years too.

This property remained in the family as brothers Johannes and Karl Wilhelm continued the family business. Sadly, Karl Wilhelm’s widow had to sell the house in 1897 because of financial problems. However, in 1979 Daimler Benz acquired the property and set about restoring and preserving the building. Today it is a museum dedicated to Gottlieb Daimler and a meeting centre for the company.

Gottlieb's mother was Wilhelmine Friderike Fensterer-Däumler, Fensterer (or Finsterer), being her maiden name. Also a native of Schorndorf, Wilhelmina was born on the 28th of March, 1803. Her father is recorded as a dyer, or a chemist, depending on sources.

As mentioned, the couple had four sons. They were not really a rich family but did all they could to ensure the boys had a good education. Gotttlieb in particular, was a considerable financial burden to his parents as he excelled at so many things, including art. Other family members of the wider family had to help so that the Dailmers' could afford for Gottlieb to attend Schorndorf Art School to develop his gift for drawing.

Even as a child Gottlieb Daimler had a thirst for knowledge and great ability to retain information. His primary education at Schorndorf Lateinschule and grammar school was completed by 1847 so the 13-year-old Gottlieb Daimler was ready to move on to trade school. Daimler's father suggested a life as a “municipal employee”, a local government employee providing administrative support to officials, or to help provide public services.

Gottlieb had other ideas. He wanted something in line with his interest in engineering which, in turn, took him into an apprenticeship as a carbine (a shorter type of rifle), maker to Master Gunsmith Hermann Raithel, in Schorndorf, starting in 1848. Gunsmith J. Chr. Wilke became Gottlieb's master. Four years of apprentice and attendance at technical school ended in 1852. Daimler’s apprenticeship craft test produced a pair of a double-barrelled pistols, suitably engraved for the era. This experience mast have given Gottlieb a thorough understanding of precision mechanics and a proper introduction to understanding and working with explosive forces, which would be most useful to him in later life.

After graduation, having learned the nuances of the gunsmith's craft, Gottlieb turned his back on that trade to pursue mechanical engineering. The industrial revolution was driving so many aspects of engineering; steam and internal combustion engines, railway and locomotive designs and machine tool making. So many options for a mechanically minded young man with a great hand for drawing. The fine tolerances of small gun parts would be replicated in the fine tolerances of much larger engineering projects. All knowledge and skills were transferable, but far more was to be learned.

The 18-year-old Daimler left home to study steam engines at the Royal trade school in Stuttgart for two years. Gottlieb enrolled at ‘Stuttgart’s Polytechnic Institute’, also known as ‘Stuttgart’s School for Advanced Training in the Industrial Arts’. At this time Gottlieb was looking to enhance his knowledge related to steam engines and locomotives.

Ever studious, Daimler also attended technical drawing classes on Sundays and obtained extra theoretical tuition that gave him a further basis for study. His hard work brought Gottlieb to the attention of Ferdinand Steinbeis, a Württemberg government councillor and very influential promoter of industrialisation in Württemberg.

Ferdinand Steinbeis connections eased Daimler into work at the "factory college" of F. Rollé und Schwilque (R&S) in Grafenstaden, in the Alsace. Steinbeis also provided for Gottlieb's scholarship and travel to Strasbourg in order for him to work and learn directly in the firm as of R&S, referred to as the “factory college” due to it being managed by Friedrich Messmer, formerly an instructor at the University of Karlsruhe. Having left Schorndorf, Gottlieb would rarely return.

Starting on the 20th of January, 1853 Gottlieb's theoretical instruction received practical experience reinforcement; and no doubt helped pay a few bills too. F. Rolle und Schwilque built machine parts when Daimler began work in the machine tool factory. His work ethic and quality saw him rise within the firm.

Daimler proved his worth to Rollé und Schwilque becoming a foreman there in 1856 aged just 22 just when the firm started producing railway locomotives.

Further extending his education in Stuttgart at the School for Advanced Training in the Industrial Arts, the 'Stuttgart Polytechnic Institute', between 1857 to 1859. Gottlieb's results from the Trade School were so good that Daimler was able to skip the first two years of the engineering course and the Polytechnic made him exempt from tuition fees. Daimler completed a whole list of subjects, demonstrating his propensity for learning. Not just the physics and chemistry, required for mechanical engineering, and the engineering itself of course, Daimler studied history, English and economics.

Having completed his broader education now Gottlieb returned to Grafenstaden in 1859. His work at R&S no longer fulfilled him. Gottlieb's in-depth grasp of steam powered locomotive engineering made him more and more convinced that the age of steam was destined to be superseded when the gas internal-combustion engines of the era became small, cheap, light and simple enough, for light industrial use. History has proved him correct. His enthusiasm for steam locomotion departed him.

Daimler left Grafenstaden in the summer of 1860, and headed to Paris to see how the French were progressing in the fields of internal-combustion engines. He studied Etienne Lenoir's two-stroke gas engine and took work in the Périn factory making band saws.

Once again Ferdinand Steinbeis created a travel scholarship fund for Gottlieb who was now convinced that an economical, small internal-combustion engine was exactly what was needed for the future of locomotion and industry.

In the autumn of 1861 Daimler moved on to Britain, then considered "the motherland of technology". He remained there until summer 1863 having worked with some of Britain's top engineering companies like Beyer, Peacock and Company of Gorton, Manchester.

Beyer himself was interested in automotive transport and visited the 1862 International Exhibition were a steam carriage was being displayed. It failed to impress him and Beyer decided producing railway locomotive manufacture, machine tools and woodworking machinery was more to his liking. After a troubled start Beyer and Peacock would go on to export locomotives and machine tools all over the world.

This expertise with machine tools that Beyer had accumulated was just the sort of technical knowledge Daimler wanted to acquire. Gottlieb too, had visited the 1862 World Fair in London, but he took a different view of automotive transport.

Apparently, Daimler also helped start engineering works in Oldham, Leeds, and Manchester (with Joseph Whitworth). He also visited a machine tool factory in Coventry, studied mechanised production as well as thread milling and shipbuilding, and spent time with two other locomotive manufacturers.

Having become deeply acquainted with British mechanical engineering and mastered the design and use of machine tools, Daimler looked to return to the continent; although he was now a confirmed Anglophile. In July, 1863, Daimler took his vast new knowledge, skills base and resources across the channel back to the continent, for a spell in Belgium.

Ferdinand Steinbeis support for Daimler continued and, together with Karlsruhe engineering works founder Emil Kessler, they 'engineered' an opening for Daimler at a Christian institution helping the socially disadvantaged; orphans, invalids, and the poor. Their focus was to give not just homes but work and education in the engineering factory of “Bruderhaus Reutlingen”.

The Reutlingen "House of Brothers" was established by Gustav Albert Werner. A philanthropic theologian, one-time priest, Christian socialist and committed social reformer, Werner created this confraternity devoted to the ideals he felt the world should have. The charismatic leader set up a paper mill, wood-working factory and engineering works all as not for profit businesses. However, even not for profit firms still have to pay their way and financial difficulties were upon them; particularly the engineering works.

Daimler joined the “Bruderhaus” as a technical manager with the challenge of bringing the works to a sustainable position. Daimler's management skills quickly effected change and returned the engineering works to profit. In return, he was elevated to an executive level and oversaw all the Werner enterprises.

The “Bruderhaus” is where Daimler first met an orphaned teenager, Wilhelm Maybach in 1865.

Daimler saw within Maybach an intelligence, inventiveness and determination to excel that he knew would take the young man far in his life.

Maybach, born in 1846 and thus twelve years Daimler's junior, was befriended and would have great consequence in Daimler-Benz history, as well as being a lifelong collaborator.

Daimler would spend the next decade working in the world of heavy engineering. As if he wasn't busy enough, Daimler spent his free time designing machinery, tools, mills, turbines, some agricultural equipment and even scales; just for fun.

Marriage and Children

If this period at the Werner Reutlingen Bruderhaus was important to Daimler for the meeting of Maybach, Gottlieb Daimler also met someone who would be even closer to his heart; one Emma Kurtz.

Gottlieb Wilhelm Daimler married Emma Pauline Kurtz, a pharmacist's daughter and native of Maulbronn, on the 9th of November 1867. The couple were to have three children, Paul Daimler b1869, Adolf Daimler b1871 and Wilhelm Daimler b1881. Sadly, Wilhelm was to pass away in 1896, aged 14. The marriage would last more than 20 years until Emma Kurtz-Daimler herself died in 1889.

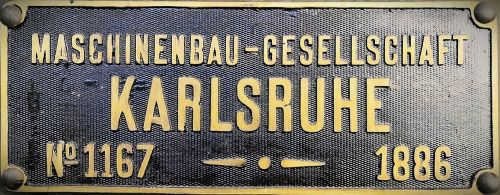

In the December of 1868, after five years at the Reutlingen Bruderhaus, Gottlieb took a new post as Workshop Manager at the Maschinenbau-Gesellschaft Karlsruhe, or Karlsruhe Mechanical Engineering Company for those wanting the name in English.

Karlsruhe engineering works, where Carl Benz had also worked as a fitter, manufactured equipment, locomotives and wagons for the railways in Baden. But the firm, originally set up in 1836 by entrepreneurs Emil Keßler and Theodor Martiensen, had been through troubled times and never really got enough Locomotive orders from the Baden state government to be properly successful. By 1868 the firm desperately needed some reorganisation and Daimler was just the man to do it.

Gottlieb's organizational skills, soon had effect and in 1869, at the age of thirty-five, became ' factory director'. Within six months Daimler had brought Maybach in, as Technical Designer, too.

Maybach's technical understanding and excellent work made the pair ideal for this sort of project and they soon had things moving in the right direction. Even through the war between Germany and France in 1870-1871 the Maschinenbau-Gesellschaft Karlsruhe was able to succeed.

Daimler and Maybach would spend much time discussing new design ideas for all manner engines for pumps, the lumber industries, and metal pressing. Their life-long partnership with the simple goal of making engines to move vehicles.

This was the point at which Daimler's name started coming to prominence and Maybach too now stood out from his peers.

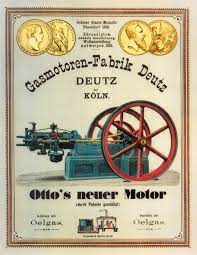

Having spent three years in Karlsruhe Daimler was approached by Carl Eugen Langen, an engineer, inventor and entrepreneur (and another graduate of the Karlsruhe Polytechnic institute), to join Gasmotoren-Fabrik Deutz and assist in the firms development of the gas engine the Belgian Etienne Lenoir had invented.

Gasmotoren-Fabrik Deutz had built a new factory in Cologne, Rhineland, to build the improved Nicolaus Otto version of the gas internal combustion engine. Langen entrusted the equipping and installation of the factory, the optimisation of the production processes and general management to Daimler in August,1872, at thirty-eight years of age. He also wanted Gottlied to institute a new specialist design and development department too.

Gottlieb Daimler's new position as technical director was given without the involvement of Nikolaus Otto who would clash with Daimler many times; though both recognised the abilities of the other, they both stubbornly thought they were correct and their ideas should take precedence. That said they were able to collaborate on a number of inventions, not least the construction of the first 100hp gas engine.

Fortunately for Daimler, Langen had relented to Daimler's insistence that Maybach be brought in to assist him and Wilhelm Maybach was brought in as chief designer in January 1873.

The Nikolaus Otto four-stroke system of internal combustion engine was key to its effectiveness, garnering him recognition worldwide for this invention. Daimler was to gain an intimate knowledge of this four-stroke principle while he helped perfected the Otto atmospheric engine. All of which reinforces the old saying, “invention begets invention.”

Daimler transformed Deutz into a world-wide renowned firm. He improved production but more importantly overcame the weaknesses of Otto's vertical piston design. In his own little workshop in Bad Cannstatt Daimler continued to follow his own designs for a small light, fast-running petrol engine that could have multiple applications. In 1875 the Deutz board did ask Daimler to work on a gasoline-powered version of Otto four-cycle engine but the idea was short-lived when the board decided to exploit their existing commercial success of the Otto engine.

Through 1876 Daimler and Maybach managed to improve the Otto engine but it remained too large and heavy. Otto continued experimentation on the four-stroke principle to understand the mechanics and fluid dynamics better. What had initially been a 1/2 hp unit that was 4m tall, and exceptionally heavy, was slowly developed to provide a 3hp output, even in a somewhat reduced size. But it remained unable to exceed 200rpm without breaking down. The optimizing of this engine design made it a best selling item capable of replacing steam engines or waterwheels; despite still being inefficient and, to our eyes, primitive. Sales figures grew as the reliability and efficiency improvements took hold. Success was just around the corner.

On the 4th of August, 1877, Otto patented the engine. However, the patent was soon challenged then overturned. Karl Benz was concentrating his efforts in Mannheim, to produce a similar concept of delivering a reliable gas engine based on the two-stroke principle. The Benz engine was ready on the 31st of December, 1878, and was granted a patent in 1879.

Otto failed to include Daimler or Maybach in the patent application, causing considerable tension between Daimler and Otto. Daimler and Maybach decided to follow their vision of a small, universally applicable engine. But what Daimler was dreaming and planning was not quite possible right then.

Up to this point his name was on the following patents:

Patent # Date Title Name Area covered

168,623 11-10-1875 Air & Gas Engine Gottlieb W. Daimler, German Empire

222,467 9-12-1879 Gas-Motor Engine Gottlieb W. Daimler, German Empire

12 -8-1879 Gas-Motor Engine Gottlieb W. Daimler, Patented in England.

232,243 14 -9-1880 Gas Motor Engine Gottlieb W.Daimler, German Empire

26 -7-1880 Gas Motor Engine Gottlieb W.Daimler, Patented in England.

The clash of ideology between Otto and Daimler grew deeper but Gottlieb Daimler was still the man Deutz-AG chose to send to Russia as their representative during September to December, 1881, in order to investigate the possibilities of exporting to Russia and to look into the then levels of industrialisation there. The transportation discomforts he endured there led him to record the following in his notebook: “I detested the overcrowded trains in the summer and the limitations imposed by the railways, which made me think of independent driving.”

On Daimler's return in December 1881 serious personal differences between Daimler and Otto continued to rise. Daimler's stubborn insistence on atmospheric engines and Otto's stubborn resistance to changing his approach created an impasse. Some have even posited that Otto was jealous of Daimler, as Gottlieb had a prestigious university background and exceptional knowledge.

What ever the reasons, in 1882 Otto put pressure on the Supervisory Board to ask Daimler to set up a Deutz-AG branch in St. Petersburg, Russia; or resign. Daimler saw little business opportunity in Russia, and a lot of travelling, so Gottlieb chose to leave Gasmotoren-Fabrik Deutz and started negotiating his exit package.

As of the 30th of June, 1882, Gottlieb Daimler left the firm. Reportedly, Gottlieb received 112,000 Gold-marks in Deutz-AG shares as compensation for termination of employment and for Daimler and Maybach being omitted from the Otto engine patents. Wilhelm Maybach also left Deutz-AG though of his own accord, apparently in September 1882, partly out of loyalty to his friend and because Daimler created a contract including "... the completion of diverse projects and the solving of mechanical engineering problems, as commissioned by Mr Daimler", which appealed to his, and Daimler's, mutual engineering interests.

Daimler was now 48 years old and had gained extensive experience from his many years of managerial positions at high level companies. He now also had the necessary financial security to set up his own business and follow his own path; with Maybach's support of course. Both men were confident in themselves and their ideas. Their pursuit of a light, high-speed engine was sure to result in a revolutionary "capital invention".

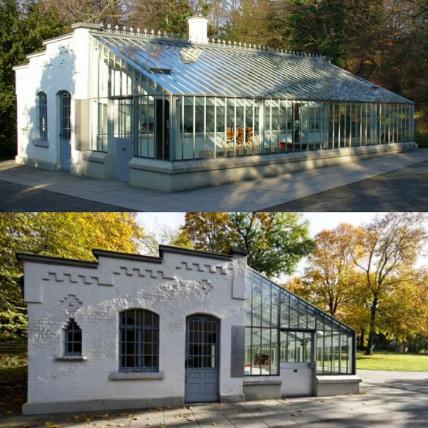

In the spring of that 1882 Daimler bought an expansive villa at 13 Taubenheimstrasse, Cannstatt, near the Royal residence in Stuttgart, Southern Germany. It cost 75,000 Goldmarks and provided an opportunity to create a working laboratory within the grounds for Daimler and Maybach to work on their engine designs together.

In the garden was a spacious summer house to which Daimler immediately added a brick annex. Within this greenhouse and extension Daimler created his and Maybach's experimental workshop. They took advantage of the opportunity to widened the garden paths into "roads" too. In the July of 1882, Daimler and his family, were able to move into their new home.

The new working facilities were laid out thus. An office containing Gottlieb's desk and a bureau, was set out in the front room. Adjoining this a light and airy room while held a workbench and a forge became the two engineers main work space. The actual design office remained, at least for the time being, at Maybach's flat in Pragstrasse, Cannstatt, where he lived with his wife Bertha.

Whatever the noise and activity there was in the garden workshop we can only guess at today, but it was certainly sufficient to cause alarm amongst the neighbours. They felt compelled to report the pair to the local police alleging Daimler and Maybach were some sort of counterfeiters. The constabulary diligently obtained a key from the gardener, in the absence Daimler et al, and proceeded to raid the house. One can only imagine what they thought when confronted with nothing but engines in various states of completion.

Having set up their workshop Daimler and Maybach focused on their dream to change the world. Their idea was, naturally, to improve on Otto's engine and devise their own engine design. Their criteria was to develop a compact, lightweight, high-speed, four-stroke, internal combustion engine. A miniaturised Otto type motor that could be installed in driving carriages, carts, rail-mounted vehicles such as locomotives and trams, boats, ships, and airships as well as put it on wheels to power agricultural equipment, fire pumps in short, every conceivable type of vehicle or purpose on land, sea or in the air.

Together, they were determined to address the weaknesses in the Otto design and build upon the strengths. Embarking on the long and painstaking process of building a reliable engine through practical work with their own hands had begun.

Despite early disappointments they were destined to reach their goal.

Pursuing his ambitious goals required Daimler and Maybach to consider many issues.

One subject of much conversation between the two men was the type of fuel to burn in their engine. Gottlieb Daimler settled on a commonly available petroleum distillate Leichtbenzin (light petrol or light gasoline). Most were used as lubricating oil, or in cleaning spirits like Ligroin (petroleum Naptha, Ligroin is derived from petroleum, the name for crude oil, not petrol, which is another derivative from “Petroleum”), another type was Kerosene (also used as lamp fuel). One of the main advantages of these “Mineral spirits” was that they were easily available from any Pharmacy. This system required a carburettor of a similar type to those on the gas engine but the one Maybach invented was much better than anything Otto had come up with.

Another was how to get an engine to revolve faster. The main reason for Otto's lack of success was his complicated slide-valve flame ignition mechanism; it simply couldn't operate fast enough. The pair went through many countries patent papers to see if they could find any clues to a solution. They did. An Englishman by the name of Watson had patented a system of hot-tube ignition, via an incandescent tube in the cylinder head, that required no control. A so-called “amorce” device to detonate the fuel. It was an advantage in that the hot tube was hot even after the heating flame had been extinguished and because the electrical systems of the time functioned too slowly and unreliably.

The concept of the four-stroke system was inevitable as both men were already familiar with this sort of principle from their time working at Deutz. To permit high engine speeds the inlet and exhaust valves needed to move faster and have a better control system. It would be decades before overhead cams and valve overlap timing would be a thing but getting them moving faster, and more reliably, was a good start.

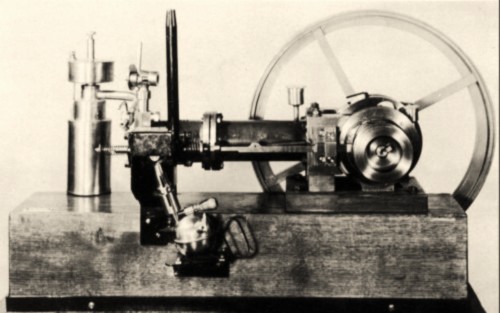

The men's first experimental engine uttered its first sounds late in the year and was running reliably in the workshop towards the end of 1883. The world’s first liquid gaseous fuel, compressed charge, four stroke engine was ready for unveiling. It was a small, horizontal engine cylinder unit. The main cylinder parts were cast by the Kurz bell-foundry. The entry in their records states the parts were for a “small model engine”, so it was relatively light compared to the huge Otto engines.

It displaced roughly 100cm³, producing around a 1/4hp @ a sensational 600rpm. Three times as fast as the Deutz gas engines 120-180rpm.

With this engines success, 14 years of effort, including this intensive experimentation year, meant Daimler and Maybach had met their first major design objectives, Daimler's “dream engine” as it was to be called, was ready to be patented.

However, although the new engine was considerably smaller than Otto's engine it looked very similar to it, to the untrained eye. And both men knew very well that Otto's four-stroke patent (DRP 532) was still valid. So, the wording of the patents would need to be very particular to avoid conflicts. Just a week after the gas engine Daimler filed for German Imperial patent DRP 28 022, with the simple title "Gas engine", among other things the basis of the application focused upon the principles of explosive ignition and rapid combustion, circumventing Otto's four-stroke principle as much as possible.

Further applications for gas engine patents under the title "Innovations to gas engines" Daimler also had a valve control patented "for regulating the power and speed of the engine" resulted in German Imperial patent DRP 28 243, which included a drawing of the engine having a vertical cylinder suggesting the ideas for future designs were already being laid out.

Successful acceptance of the patents came on the 16th of December, 1883, and would spark bitter legal disputes with Otto and his Deutz company. Daimler declined to allow Deutz free user rights for the hot-tube ignition system and Otto started a patent war through the courts. After lengthy disputes Daimler made a personal appearance at the courts and his arguments persuaded the court to support his patents.

Technical Director Daimler and chief designer Maybach, had delivered the first high-speed engine usable in transportation applications. Patent as a reliable uncooled, heat-insulated, high-speed engine with a self-firing ignition system by unregulated hot-tube.

Of course, that first triumph was just the beginning of a long journey of development and improvement. With the legal action by Otto in the background, Daimler and Maybach had to differentiate their engine from the Otto model. Together they perfected a new, more efficient and even smaller engine.

On the 3rd of April, 1885, a "gas or petroleum engine" was registered by Daimler as German Imperial patent No. 34926 and put Daimler's vision in the public domain. It still used the four-stroke, internal-combustion principle, but now looked totally different to the Otto engine. The single-cylinder engine was moved from the horizontal position to the vertical. It now sat, for the first time, on top of an enclosed crankcase. It held lubricating oil and kept out dirt and dust. This was the famed Standuhr, or "grandfather clock", engine as it looked so much like the late 19th Century pendulum timepieces.

It had a host of features which to us might seem obvious, but when you're breaking new ground each step is less easier to see coming. The cylinder was cooled by air flanges, and while the intake valve functioned automatically, the exhaust valve was operated by a curved groove control invented by Daimler, which also helped to keep the revolutions in check.

Driven by gasoline a carburettor was required, Daimler recorded an patent application for a new surface carburettor as "apparatus for vaporising petroleum for petroleum engines", on the 25th of March, 1886. Hot-tube ignition remained the ignition source of choice, and would remain Daimler system until 1897 when the Bosch electrical ignition was perfected. Even with all the main working parts enclosed within the engine casing this upright engine weighed just 60kg and despite its small size still produced 1hp (0.7kW) @ 600rpm revving up to an astonishing 900rpm.

One feature that didn't last was a piston crown valve to assist the charging still further, not as useful as it was expected it is an example of the thoughtfulness and lengths to which Maybach and Daimler were experimenting.

Daimler built three engines to this design in 1884, one of which was a scaled down version and had a cast iron flywheel attached. While the “grandfather clock” engine design was recorded in the history of technology, the one with the flywheel would have an even greater claim to fame; as we shall see in the next years evolution.

The Daimler-Maybach team spent most of 1885 building the low weight, compact, engine that was usable for their revolution in transportation. They now had to see if their engine design could actually move a vehicle.

Gottlieb Daimler's 1885 patents include the “Reitwagen”, the world's first true motorcycle. Other people had put steam engines into two wheel frames earlier but this was the first gasoline-driven internal combustion engine to power a two wheeled machine. This patent was granted on the 28th of August, 1885, for a "Vehicle with gas or petroleum drive machine", patent no. DRP 36423.

Daimler did patent an engine design in 1885 too. Patent #168,623 was issued for an Air & Gas Engine under the name of Gottlieb Wilhelm Daimler enforceable throughout German Empire.

It is generally thought that it was Wilhelm Maybach who came up with the idea of a two-wheeler to test the theory rather than Daimler. A cheap, cost-effective workaday test vehicle makes the most sense in business terms, as well as practicalities of weight conservation too.

Essentially a wooden bicycle frame with foot pedals removed, but two small spring-loaded outrigger wheels added, the Daimler Reitwagen ("riding wagon") or Einspur ("single track") was around 50kg (110 lb) in weight and stood 76cm (30in) tall. It is a hot bed of ideas and was really a stepping stone in Daimler and Maybach's route to creating a motor car.

Daimler initially designed steering linkage shafts with right-angle bends connected by gears but this was simplified on the working design to a simple handlebar with a twist grip for controls.

The engine was an air cooled upright single cylinder four-stroke engine of 264-cubic-centimetre (16.1cu in) mounted on rubber blocks to the wooden frame. Power output was rated at 0.5 horsepower (0.37kW) running at 600rpm translated to a top speed of about 7mph (11km/h). The design had two flywheels and an aluminium crankcase. A float metered carburettor fed fuel through mushroom shaped intake valves, opened by the suction of the piston's intake stroke, and ignited by a hot platinum tube which had an open flame at the outside end which radiated white hot heat through and into the combustion chamber. It was also able to run on coal gas and due to the experimental nature of the machine is rumoured to have later been fitted with a spray-type carburettor. The exhaust valves were cam operated allowing for high speed coordinated operation.

Drive to the rear of two wooden wheels with iron tyres was via a belt drive. The twist grip on the handle bar served a dual purpose. When turned one way it released the brake and tensioned the drive belt thus applying force to the rear wheel and of course motion. When the twist grip was turned back the other way it loosened the drive belt and reapplied the brake, thus slowing and eventually stopping the machine.

There are conflicting versions of the first trials of the Daimler Reitwagen, this may be due to confusion due to circumstances. We'll do our best to cover both as they hold interesting substance in each case.

On November 10th, 1885, Daimler's 17-year-old son, Paul, rode it a fair distance, estimated as somewhere between 5–12 kilometres (3.1–7.5mi) on the road from Cannstatt to Untertürkheim. A flaw in the design was the positioning of the hot tube burner under the seat, this set the saddle on fire and the machine was reduced to ashes.

Paul Daimler (13-9-1869 to15-12-1945 and eldest child of Gottlieb Daimler), himself became a mechanical engineer and car designer. He studied at Technische Hochschule Stuttgart and worked with his father in the Cannstatt factory. In 1902 Paul joined the Austro-Daimler firm eventually becoming technical director where he go on to design an armoured car. He clearly had his father's intuative engineering mind and would go on to have a great career in his own right. Technical Director of Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft between 1907 to 1922 covering Untertürkheim, Sindelfingen and Berlin-Marienfelde. After which he joined Horch and proved himself as an aero engine designer and developer. He introduced hydraulic valve lifters in 1931.

It is also recorded that Wilhelm Maybach drove the Reitwagen from Cannstatt to Untertürkheim for 3km alongside the river Neckar on the 18th of November, 1885, reaching 12 kilometres per hour (7mph). Most drawings of the era show Maybach portrayed either riding or beside the machine. But due to the fire and a subsequent built machine of similar design there may simply have been two 'firsts'.

The design was refined through the winter of 1885–1886, and a second machine was built featuring a belt drive with two-stage, two-speed transmission with a belt primary drive and the final drive using a ring gear on the back wheel. It is also reported the machine was driven by Paul in Mannheim, Baden.

The confusion is clear, but it may also be possible that both men were at all the test runs of the Reitwagen where ever they occurred. Either way, having served it's purpose as a test bed for motor car ideas ,the Reitwagen project was put aside in favour of putting the motor into a larger multi wheeled car.

Fire was once again to claim the Reitwagen when a blaze destroyed the Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft Seelberg-Cannstatt plant in 1903. However several replicas have been built and now reside in collections around the world.”

At the end of the day the bragging rights for designing and building the world's first controllable, petrol powered internal combustion engine motorcycle remain with Daimler and Maybach. During the following decade many other self-propelled bicycles designs would become public.

1885 had seen this revolutionary engine prove the concept of engines moving vehicles. Daimler then produced them as the first commercially practical gasoline engines, and assisted Messrs. Crossley, of Manchester, in their gas engine designs. The revolutionary design steps of the year put Daimler and Maybach well ahead of their competitors and gave them the time and funds to explore the next stages of the development to build a universally adaptable engine.

Daimler was already working on fitting one of his engines, a more powerful, water-cooled version, in a horse-drawn carriage. The next year was to see Daimler's plans to power transport come to fruition.

Having created a reliable engine and proved it could move a motorcycle, the renowned inventors now needed to find commercial uses for it, so, Daimler and Maybach set about putting an engine into a carriage.

After making the necessary assessments Maybach oversaw the installation of a new version of the single cylinder “Grandfather Clock” engine at the Maschinenfabrik Esslingen during October 1886. The new engine was a larger 1.1hp, 462cc (28cu'in) running at up to 900rpm. Despite being larger the unit still weighed no more than 40kg and was mounted on the floor between the rows of seats. Power was transferred to the rear wheels by means of a set of dual-ratio belts.

With all the various work delays with the new Daimler “Motorkutsche”, or motor carriage, meant to be the precursor of the four-wheeled motor car, the machine didn't actually start running on test until 1887/88. Sixty miles away in Mannheim, Carl Benz had already got his entirely original three-wheeled motor car running and received his patent for it on the 29th of January, 1886. But when Daimler and Maybach did get the car on the test track (well, the same road up to Untertürkheim that the Reitwagen was tested on), it managed an impressive 16kph, or 10mph if you prefer.

The Daimler four-wheeled Motorkutsche was the world’s first four-wheeled automobile, despite very much being a horse drawn carriage with an engine. It secured a place in automotive history for Daimler and, after the Reitwagen, further proved the concept of automotive transportation. More practical than the Benz design, but less original or innovative, the ‘Daimler motor carriage’ represented the idea of the four seat petrol engined motor car, and future direction of a concept which would end in a global automotive empire.

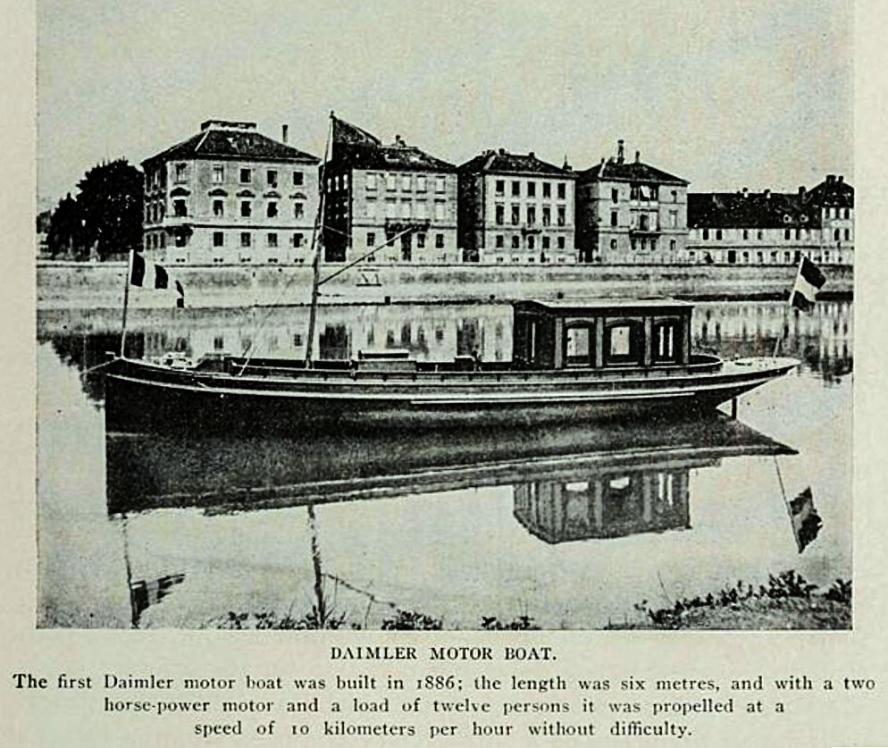

In the mean time, Daimler and Maybach were working elsewhere to the same ends. They were really very consistent in their plans to use their engine in as many ways as possible, and took their motor to transportation other than on the roads. One area of well established transportation was shipping. As such the automotive dynamic duo fitted their lightweight motor to a launch.

Daimler acquired a 4.5m long boat and installed one of their petrol engines into it. The motor launch was named “Neckar” after the River Neckar, near Cannstatt, on which it was tested. It may have been an experimental launch but it achieved a speed of 6 knots, equating to 11kph or 6.9mph.

The world's first motorboat generated a fair amount of interest but early prospective customers were somewhat concerned that a petrol engine was more likely to explode. Daimler invited people to take a trip on the launch but hid the engine under a ceramic cover and called it an "oil-electrical" motor. Achieving a Patent for a "machine to drive the propeller shaft of a ship by either gas or petroleum-powered engine", no. DRP 39-367 on the 9th of October, 1886, the motor launch was a success and marine engines soon became one of Daimler's main products; something that continued well into the 1900s.

Daimler and Maybach's diverse activities were being recognised further afield now, prompting an automotive and engine powered revolution in France and England, and prompting wire-wheeled gas powered motorised vehicles in America.

But that does not mean everything was Rosie. During 1896 Daimler sued Benz & Cie because they had violated the 1883 patent on hot tube ignition belonging to Daimler. The Mannheim courts found in favour of Daimler and Benz was required to pay royalties. Daimler and Benz had gradually become fierce adversaries and never actually met each other. Even during the Central European Motor Car Association's founding the pair never spoke to each other.

However, with marine and stationary engines selling well it was becoming clear that Daimler's garden summer house workshop was gradually becoming unable to keep up with demand.

The “Necker” garnered much attention as did the continued road tests of the four wheeled Motorkutsche. Daimler was becoming more aware of this sort of soft advertising and wanted to take every opportunity to show the wide variety of uses his engine could have. This action proved to be effective and engine sales increased to the point that Daimler had to find a more suitable manufacturing plant to satisfy the demand for engines.

On the 5th of July, 1887, Daimler bought a new workshop, quite near his home, at 67, Ludwigstraße (today Kreuznacher Strasse), on Seelberg hill, Cannstatt. Apparently, Cannstatt's mayor was not inclined toward industrial workshops in the town and so the premises, formerly the 2,903 square meter metal foundry and nickel-plating works of Zeitler & Missel and costing 30,200 gold marks, was a good way out of the town itself.

Daimler designed and patented a miniature tram type railway that ran from the Cannstatt spa hall ("Kursaal"), and Wilhelmsplatz. This motor street car, propelled by a single cylinder engine and having three pairs of interlocking wheels in a sort of gear system to change speeds as required, ran on steel tracks and was all done with the backing of the town council. This transport system was very popular and soon featuring in other towns too.

Engine production in a factory on Seelberg hill, primarily for motorboats, was soon up and running. Maybach's home design studio now moved to new engineering design offices, Gottlieb Daimler managed commercial issues with is personal assistant Karl Linck, who took care of the day-to-day bookkeeping and correspondence. 23 new employees were carefully selected according to their particular skills by Daimler. However, the wage bill of so many new workers soon ate through Daimler’s private resources, despite good profits from the engine sales. It might be simplistic to say but the business was still in its early days and may have expanded a little beyond its means at the time. Forced to seek investors Daimler turned to Max Duttenhofer, director general of Köln-Rottweiler Pulverfabrik, and his business associate Wilhelm Lorenz of Karlsruher Metallpatronenfabrik (Cologne-Rottweil powder works). This created the new company of Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft, or "Daimler Motor Corporation."

Daimler and Maybach were well into their plan to put engines into vehicles on land and water. The third arm of the three pointed star now beckoned.

Leipzig bookseller Dr Friedrich Hermann Wölfert had designed a balloon with a hand operated driving system to steer and propel it at will. Then, working with Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft, a Daimler single-cylinder 2hp/1.5kW @ 700rpm engine was fitted to cut down on the manual labour.

In the calm weather of the 10th of August, 1888, Dr Wölfert flew his dirigible balloon from the DMG factory yard on the Seelberg hill, Cannstatt, towards Kornwestheim. Four kilometres Dr Wölfert returned the first motorized airship, safely, to the ground, in the intended landing area of Kornwestheim.

Daimler engines had now conquered the land, water, and air.

Another pioneering move for Daimler and Maybach was the answer to a common firefighting problem of the time. When called out the fire crew could hitch up their steam fire engine to the horses and race off to the scene. On arrival they would then bring the steam up to pressure while assessing the fire. The problem was the steam pressure could take as much as 15 minutes to reach operating pressure; all the fire crew could do was pump by hand (if they still had that option on their machine), use small gas powered canaster fire extinguishers, and watch as the fire damage mounted up. The dire consequences of this delay had been felt in the1842 “Great fire of Hamburg”, in which as much as a third of the city was destroyed. It became clear to everyone across Europe that intervention before the fire could take hold was vital.

Germany's first professional “Feuerwehr” (fire brigade), was formed in 1851 in Berlin. However it is recorded in the Karlsruhe municipal council records of the 24th August 1847 that a fire brigade was constituted there under the French name of “Pompiercorps”; which is still the name of the firefighting force there today.

With all this in mind, and being ever alert to any new operational opportunity where his engines could make a positive impact on life, Gottlieb Daimler was open to the idea of Heinrich Kurtz to fit one of Daimler's engines to a fire-fighting pump thus eliminating the 15 minute warm up time, getting to work straight away, and it could sustain that effort for as long as necessary. Kurtz had made the engine castings for Daimler's first engine a few years earlier, and not only cast bells at his foundry but was a fire-fighting pump manufacturer too. Heinrich Kurtz supplied the base carriage with piston water pump to Daimler and Gottlieb mounted a single-cylinder 1hp motor to the appliance by a small additional gear adaption to connect the motor to the piston pump. The carriage remained the horse-drawn type which could be quickly harness up should an emergency occur. This was the first step towards the modern motorised fire appliances but it was just one small step.

Daimler filed their patent application for an engine-driven fire-fighting pump on the 29th of July, 1888, at the Imperial Patent Office in Berlin. German Imperial Patent No. 46779, in class 59 was eventually granted on April 15, 1889. Daimler would go on to develop the idea much further but in the mean time displayed this innovation at fire trade events around Europe, which inevitably led to worldwide attention.

The single-cylinder engine, while competent for some uses was clearly underpowered for other potential applications. During 1888, Daimler and Maybach started work on two-cylinder engine and a new vehicle design of their own, front to rear, top to bottom, and not a converted horse drawn carriage. Presumably, the continuous tests of the early motor carriage, and new engine tests, as well as other adaptive initiatives, were the basis for the often reported sightings of Daimler excursions along their now favoured test route of the road to Untertürkheim. Such tests would thus end in the new design and Daimler himself applying for a driving permit for a "light four-seater chaise with a small engine" on the 17th of July, 1888; which some have suggested was the first driving license.

Interestingly this car design was not built in Germany as production of engines was prioritised, but it did have an impact on the development of the automobile industry elsewhere. Maybach and Daimler presented their "V " design engine at the October 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle. Panhard and Levassor had links with DMG already but now Peugeot became interested in the DMG engine too. The Daimler Stahlradwagen and the V-twin engine was licensed to be built in France; the later featuring heavily in motor car designs there.

The general public took little notice of the Stahlradwagen and in commercial terms it wasn't successful, however it did cement Daimler's firm in the automotive industries collective psyche. By 1891 Panhard and Lavassor were producing cars with Daimler engines, as were Peugeot. In the USA Daimler engines were being built by the piano manufacturer, William Steinway, as early as September, 1888. He helped set up a Daimler Motor Company on Long Island, New York state. Steinway had the patent rights for USA and Canada but production only ran from 1891 to November 1896 when Steinway passed away.

Importantly the money made from the various licencing deals helped Daimler going forward. The new 17 degree V-twin engine set the bench mark for all car engines and also opened the door to new applications. As well as the proven markets of boat engines and stationary engine applications, road transport usage was increasing and the addition power made it much more useful for trams and trolleybus applications.

After 20 years of marital bliss, Daimler's first wife Emma Kurtz Daimler died on July 28, 1889. A sad time for all the family and close friends in the DMG circle.

On the surface things looked good at the start of 1890. Demand for engines was growing, Daimler now had distributors in London and New York, and there were increasing markets to move into. However, the small firm still could not build and sell enough engines to stay ahead of their overheads. Financial troubles continued to rise.

Despite the firms lack of liquidity Daimler had resisted having more partners, or taking the company public for many years. Friends had encouraged Daimler to do so and even his late wife had supported their ideas, seeking more security for their children's future. Daimler remained resistant because he had seen other engineers lose control of their company's and even been forced out of their own firms. He wasn't wrong either, this is a repeating occurrence remembering this happened to many famous inventors such as Karl Benz, August Horch, Henry Ford and Ransom E. Olds.

Two of those friends lobbying for more financial input were Max von Duttenhofer and Wilhelm Lorenz. Von Duttenhofer had taken over his father's powder mill and expanded it into the successful Cologne-Rottweil powder works producing smokeless gunpowder, a huge advance in military technology. Wilhelm Lorenz was also a producer of munitions as chairman of the Karlsruhe cartridge factory. Duttenhofer and Lorenz were supported by an influential banker Kilian von Steiner and the three men eventually convinced Daimler to agree to a pre-contract supposedly to safeguard Daimler and Maybach's inventions, on the 14th of March, 1890.

After further negotiations Gottlieb Daimler's "pact with the devil" was enacted on the 28th of November, 1890, with the public incorporation of the "Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft". The shares were divided equally three ways, Duttenhofer and Lorenz putting in a combined 400,000 Marks to own 200 shares each, with Daimler's 200 shares being made up of capital and the production premises, tooling, inventions etc. However, Daimler hadn't realised he was now vulnerable to being outvoted whenever it suited Duttenhofer and Lorenz.

Furthermore, promises that Maybach, as the Chief Engineer of DMG, and Karl Linck, Daimler’s accountant and head of marketing, would be on the board of management, were reneged upon causing great tension between all parties.

Duttenhofer’s principal goal was to grow DMG into a much lager firm, if necessary by merging with Daimler's competitor Gasmotorenwerke Deutz, so that Duttenhofer and Lorenz could make a profit on their investment. The method was the continued production of high speed engines at Seelberg with an expansion plan to increase the output. Daimler's idea to develop and build motor cars was much diminished as Duttenhofer and Lorenz remained sceptical toward the commercial success of cars and motorised transport.

While Daimler struggles with the finances and politics Wilhelm Maybach was masterminding another epoch-making invention. Still seeking more power output he had moved on from the V-twin engine to something bigger. 1890 saw the his new engine for boats, a four cylinder inline design that could deliver as much as 5hp (3.7kW) @ 620rpm. Maybach worked tirelessly to improve all the components, particularly those of the ignition and cooling systems.

Under Duttenhofer & Lorenz DMG's expansion came with changes and problems for Daimler and Maybach. Duttenhofer clashed with them over the way the company should move forward. Daimler and Maybach preferred to focus on the development and production of transportation itself, while Duttenhofer and Lorenz favoured production of stationary engines for commercial reasons.

An example of the general German air negativity and scepticism towards the automobile is that Daimler's progressive engine designs were pressed into use as automobile engines in France, not Germany. Neither Duttenhofer or Lorenz saw any future in motorcars and authorised the increasing of stationary engine production capacity. The workers roster rose from 22, to 163, within 12 months.

Daimler only had on third of the votes now and Duttenhofer & Lorenz reneged on the promise to include Wilhelm Maybach on the board of directors. They held the power, not Daimler and Maybach. Maybach held the title of Technical Director as created envisaged in the shareholder syndicate agreement wasn't on the board of Directors and held no shares', leading to a dispute between him and the newcomers. The contract conditions were unacceptable to a specialist of Maybach’s stature left the company on the 11th of February, 1891.

This proved a mistake for DMG. Maybach’s successor, Max Schrödter, understood very little about the internal combustion engine. Equally, the new workforce proved to be unqualified and lacking experience in complex mechanical engineering work required for engine building. Predictably the result was a fall in production figures and quality. DMG were very quickly marketing inferior products, and complaints from customers rose.

Daimler tried to stop this trend but was pushed aside. Seeing no way to reach any compromise agreement with the other partners, Daimler was relegated to a Deputy Member of the supervisory board of DMG from 1891 to 1894 though.

Daimler and Maybach, with their workers, came up with various motor car designs and solved a number of difficult puzzles resulting in the Phönix (Phoenix), engine so enamoured of Panhard and Levassor. It was a highly efficient 4-stroke, two cylinder engine, but the “V” had morphed back to a side by side, in-line design with the vertically arranged cylinders cast in one block. This unit would go on to be a stalwart base to many of DMG's future car and commercial vehicle designs. When it did hit the market in the 1895 Daimler car (a rather ugly vehicle), it could provide a power output between 2hp (1.5kW) and 7.5/8hp (5.5/5.9 kW).

All this industry and experimentation put Daimler and Maybach well on the way to producing a new four-wheel motor vehicle featuring the Phoenix engine and belt-drive.

Now fully aware of his business partners intentions Daimler was convinced he had made a mistake joining with Duttenhofer and Lorenz. So, he sort to re-establish his relationship with Maybach. Gottlieb had seen another option and had agreed a secret contract with Maybach to ensure their work continued independently of DMG as early as 1891.

Daimler began to secretly siphon funds away from DMG and eventually convinced the board an independent Research and Development allied to DMG would be a good thing to help them keep ahead of the competition. DMG would provide some financing and Maybach would be free to develop the initiative as he saw fit. This compromise to keep Maybach on side also avoided any compensation package that would surely have cut into the new firms capital with so many patents having Maybach's name included in them.

Initially Maybach worked from home as a freelance designer, his house in Cannstatt pressed into service as a design studio, with Daimler's support.

In the autumn of 1892 Daimler was able to get a lease on the former Hermann Hotel in Cannstatt which was vacant. Here they could use the ballroom, and winter garden conservatory, as workshops for 12 employees and five apprentices. As chief designer Wilhelm Maybach steered the workers in concentrating on technical improvements to engines and other commercial development projects. Any patents Maybach came up with would stay in his name to protect him from DMG, and keep the project secret.

Fundamental research into toothed gear systems, belt drive and chain drive experimentation, improvements to engine cooling systems and new spray-nozzle carburettors were all undertaken.

DMG, Daimler and Maybach co-operated in this manner right through until 1895, DMG focusing on the stationary engine business and Maybach on developing the future products including motorcars. Maybach's work would eventually prove to be very beneficial to DMG not too many years later.

A major milestone for Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft was the sale of their first car. Developed from the 1889 steel-wheeled car by chief designer Max Schroedter, the new car does exhibit a familial look, particularly in the frame. A 1,060cc two-cylinder engine sat inconspicuously within the bodywork, built by Otto Nägele the Stuttgart coach-builder. The motor could put out as much as 2hp @ 700rpm, which was transmitted through a 3-speed gearbox to the differential of the still solidly mounted rear-axle via a large gearwheel and chain drive. Altogether that was good enough to propel the vehicle at a top speed of 18kph. The engine coolant once again flowed through the tubular chassis frame as it had with the steel-wheeled car. Braking was provided through a break block which clamped down on the solid rubber tyres provided by “Hamburger Gummiwerk”.

In 1892 this innovative mode of transport was a rare and expensive plaything that only a very few illustrious clients could afford. Given that it would take another three years to have built just twelve of these highly exclusive automobiles. One might think such an important 1st sale might have warranted a less understated, matter-of-fact entry in the 1892 DMG order book than just “Sultan, Morocco”.

The company’s first customer was Mulai al-Hassan the 1st, the Alawid dynasty ruler of Morocco, who took delivery of his new automobile on the 31st of August, 1892. Prior to that his public appearances were courtesy of his noble horses. The Sultan's car looked rather different to those which ran on the European roads, mostly because of the climatic differences between Europe and North Africa. This car would have an ornate velvet sun canopy with tassels of gold thread. Ebony trim and other special refinements gave this already unique item for the time, an individuality that would stand out even more.

Furthermore, Mulai al-Hassan 1 was taken with the machine he also had a DMG motor boat too. Technological wonders of the time which must have surely impressed all who saw them. It is also befitting that one of the world's top luxury car company's first customers were Royalty, proving DMG's dedication to the most exacting of standards is nothing new but was instilled from their very first car. And gives Mercedes-Benz the right to call themselves the world’s oldest luxury car manufacturer.

An improved version the Daimler petrol powered fire appliance was shown to the world in 1892. Horse-drawn chassis with drawbar steering but a very recognisable handbrake lever beside the drivers box seating at the front. In the station the drawbars are stowed at the side, on top of the suction hoses; close at hand for attachment when when the horses are all tacked-up. Lighting is by the usual carriage lanterns fitted one each side at the front. For warning purposes the classic hand bell is mounted on a pole in easy reach of the front passenger.

The rear sheet metal housing is quite tall from the chassis and houses the twin cylinder engine used to power the firefighting water pump. The piston water pump is mounted in the centre of the vehicle. Pulse equalising tanks help smooth the piston pumping effect to provide a steady stream at the branch. Almost instantly, 300 litres of water per minute could be delivered to a fire. There was a suction hose fitting on the right and side allowed for raising water from rivers and ponds, the high pressure out put was on the left hand side through a cleverly mounted hose reel system that could be released from it's ratchets to run out smoothly to the fire; before letting any water into the hose!

This very advanced system (at least for 1892 it was), was effective in practice. Proved when a large fire in a Cannstat bed factory broke out and Daimler's engine provided 5hrs of continuous pumping, through 150m of hose, and still had enough pressure to to put water up into the 20m high roof spaces. To put this into perspective, this sort of performance would have needed at least 32 to achieve if an energy-sapping manual pump had been in use. The Daimler engine had proved its potential once again.

Word soon spread about the effectiveness of the pump and Daimler went on to exhibit the invention in a host of European cities. The next year he sent one out to the Chicago World Exposition. In 1896 the Erfurt professional fire brigade purchased a Daimler fire appliance for 5610 marks. This 10hp pump was still giving reliable service 25years later.

The biggest advance in fire pumps wouldn't come about until the centrifugal pump came onto the market. That system was not only more efficient, and provided a constant pressure, it could pump a water jet as much as twice as high as the piston pressure pump. But for the 1890s, Daimlers idea was innovative, practical and proven.

Interestingly, even as late as 1910 some fire brigade chiefs disagreed that a petrol engine to drive a fire alliance, as well as power its pump, would be advantageous over horses.

The result of this trip, had a rather different effect on his heart than that which was intended. In Florence, Gottlieb met Lina Hartmann (née Schwend), whom he had apparently met some time before when visiting friends in Cannstatt. She was the widow now and the hotel where he was staying had passed into her hands when her husband had died. Although she was 22 years his junior Gottlieb Daimler was enamoured of her and she was considered to be wise. Que, a significant change in Gottlieb's personal life.

The couple decided to marry, and at the Schwäbisch Hall on the 8th of July 1893, Lina became Gottlieb's second wife. The couple would go on to add two more children to the family. Gottlieb Daimler b1894 and Emilie Daimler b1897. Tragedy would befall one of their children too. Leutnant Gottlieb Daimler was killed on the 4th of June, 1916, at Ypres, West Flanders, Belgium. He was just 21 years old.

Lina and Daimler travelled to North America for a honeymoon trip; I'm sure the fact the World Exposition was being held in Chicago was pure coincidence. Anyway, Daimler's licensee since 1888, William Steinway, had arranged to display DMG products, including the Maybach designed wire wheel car, and the couple did go along to the event. Incidentally, that is alleged to be the first car shown in USA.

While Daimler was away things continued to deteriorate at DMG. Staff reductions and a downsizing of the design department by moving it to Lorenz's factory in Karlsruhe did nothing to stop the downward trend. DMG was now in debt to the tune of 400,000 Gold marks, completely wiping out the firms profits of the proceeding two years.

Duttenhofer and Lorenz took a 385,000 Marks bank loan without the knowledge of Gottlieb Daimler. When Daimler returned to the firm that bore his name disputes with Duttenhofer and Lorenz and continued. Daimler vowed to regain control of his company but an opportunity to do so failed when his attempt to purchase an extra 120 shares was thwarted. Duttenhofer had grabbed the majority shareholding and forced Daimler out of his position as technical director. In the face of the firms problems the bank insisted the loan be repaid. The other directors came together and told Daimler of the company's imminent bankruptcy, they insisted Daimler pay DMG's debts, or sell them all his shares and the rights to all his patents of the last 30 years.

In short sell up or we'll let DMG go bankrupt. Daimler couldn't let DMG go to dogs or risk his name being linked with bankruptcy. So, Daimler relented, resigned and accepted 66,666Marks for his shares and patents.

Duttenhofer and Lorenz were rid of Daimler, but had stifled any new technical progress. Continuing to flounder and carrying debts of 385,000 marks, the business was faltering badly. International distributors for DMG, most notably British inventor Frederick Richard Simms, started lobbying for the return of Daimler and Maybach.

Simms had seen the developments in French motor industry and wanted a license to build, rather than buy, Daimler engines for the motor boats he was selling on the Thames. Simms ramped up his pressure offering to pay 350,000 marks for the licence; as long as Daimler and Maybach were brought back into DMG first.

With DMG's situation getting worse but the day Duttenhofer and Lorenz had no other financial options to fall back on. They had to swallow their disappointment and try to lure Daimler and Maybach, back. A role as DMG's inspector general, agreement for further company reorganisation, and a large compensation package 200,000 gold marks in shares, plus a 100,000 bonus secured Daimler's reinstatement at the firm. For Maybach, who was busy with his son Paul designing at the Hermann Hotel site full reinstatement needed something different. Maybach wanted his place on the Board of Directors, as technical director of DMG, and received 30,000 shares too.

DMG was relaunched after the corporate reorganization and almost immediately started to reverse its fortunes. And within a decade Simms had put Daimler engine in a steel cover vehicle and created the world's first armoured car; oh the follies of men.

Another 1894 event that probably helped DMG's image was the Paris-to-Rouen reliability trial. Held on Sunday the 22nd of July the 126km organised by French newspaper Le Petit Journal. Envisaged as a way to stimulate public interest in the motor car and showcase the French automobile industry, the long-distance reliability trial was preceded by qualifying events and exhibitions drawing in huge excited crowds, and high newspaper sales too as sport was well known as a circulation booster.

Of the 102 entries only 21 vehicles passed the qualifying tests. Of those starters, 17 made it to the finish. In true motor racing fashion the first vehicle to the finish, a De Dion steam tractor, was demoted due to needing a stoker as well as a driver. As such, the 1st prize was shared between a Panhard & Levassor and a Peugeot, both of which had Daimler engines. In fact, all but one of the petrol engined finishers had Daimler motors, the remaining one was, perhaps predictably, a Benz.

While all the political side played out at DMG, Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach, with Paul Daimler assisting, continued to work on their engine development programs at the Hermann Hotel. The initial two-cylinder Phoenix engine was the basis for an innovative ground breaking four-cylinder engine, the third incarnation of the Phoenix engine. The development of the new engine design included several advanced features. The four cylinders were cast in one block arranged inline, and vertically. Maybach's 1893 patented spray nozzle carburettor was used and a new system of exhaust valve control via a camshaft sped up the rate of engine revolutions (rpm) above any that they had achieved before.

This four-cylinder engine was a strong and reliable as the two cylinder unit had been, and represented a significant advance in engine technology. What had initially been a motorboat engine was now a robust engine for automobiles and would become a significant racing car engine too. A major development that was key in re-establishing DMG through the attention it attracted worldwide. Daimler was the name on the lips of everyone interested in engines.

With Daimler returned to full control, and Maybach as chief engineer, an uncertain cessation of hostilities allowed for an enormous upturn in DMG's fortunes. The success of the Paris-to-Rouen trial event certainly didn't hurt either. Daimler and Maybach put their energy into driving the firm forward with the implementation of the advances made by Maybach at the Hermann Hotel facility. Which were of great advantage at that time in restoring the firm to competitiveness and rebuilding their reputation for reliability.

In fact, by the end century Daimler engines and influences were going worldwide. In France the Panhard & Levassor and Peugeot licenses had been running from 1990, and in the USA Steinway too had ongoing licences. Simms, and the Daimler syndicate, had the UK licenses from 1996. 1996 was the year Henry Ford, also seeing the prospects of automotive transport, produced his gasoline enigned first motor car. Daimler's engines prompted Giovanni Agnelli to form Fabbrica Italiana Automobile di Torino, in 1899 and the German Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft subsidiary Austro-Daimler was founded in 1899 too.

Daimler and Maybach's vision oversaw the firm produce their 1,000th engine in 1895 but new ideas were coming out of the company too. The Riemenwagen (belt car), developed at the Hermann Hotel, proved to be very popular and one of them became the first car ply for trade as a taxi; no doubt starting the popular belief that only reliable cars are ever used as taxi's. This design had the new spray carburettor, and the twin-cylinder engine had a 2.5:1 compression ratio. A new system of lubrication which scavenged oil from the crankcase and fed it back into the system. The 4-speed belt drive system gave the car it's name as well as it's drive but perhaps more importantly this was the first Daimler with a steering wheel rather than a tiller.

Daimler also also exhibited their latest fire-fighting pump in Tunbridge Wells, England, at 1895 "Horseless Carriage Exhibition". It was presented to a “stunned public” by the Daimler Motor Syndicate Ltd. In the hands of Evelyn Ellis and Frederick R. Simms.

Whether Daimler knew about one of their cars being used as a taxi isn't clear but in 1896 Daimler put the first cargo truck design out into the world when the Daimler Motor “Lastwagen” took to the roads. The project vehicle looked very much like a horse drawn cargo wagon but with addaptions to the fron drawbar steering and an engine underslung at the rear.

When the Lastwagen went into production the engine was moved to the front of the vehicle ahead of the raised driving seat. The twin-cylinder engine produced 4hp. The engines belt drive provided power to a transverse shaft at the rear which had planetary gears on each end. These gears linked in with large gear rings on the rear wheels. These vehicles were soon proving to be very popular in Britain where breweries used them to make their beer deliveries to local pubs.

Still working, now just three years prior to his death, Gottlieb Daimler was enjoying being Chairman of the Supervisory Board of DMG.

His Company was developing products and ideas that were driving the world and in 1897 that meant putting into production the first road vehicles with four cylinder engines. The latest Phoenix-Wagen in standard form had an in-line two cylinder mono-block engine of 1060cc, capable of 4hp @ 700rpm. The block now sat on a spherical shape housing enclosing the crankshaft. Customers could order the car with other engine sizes though, a smaller 2.3hp twin or the larger 6hp four-cylinder engine. Belt drive gave way to chain drive through a 4-speed geared transmission unit and the adoption of Bosch electrical magnetic low voltage ignition replace the old hot tube ignition system. Another new feature was the use of steel U-section framing to build the chassis. The new car also had a new style. Although the cooling radiator was low slung at the rear the engine was mounted between the chassis rails at the front. Covering the engine was a sheet steel bonnet and the vehicle now looked decidedly different to any that had come before, in no way did it look like a horse drawn carriage or wagon at all.

This new Phoenix-Wagen passenger car replaced the Riemenwagen pretty quickly and is thought to be the first motor car to be able to reach a top speed of 25kph. Still only about half the speed the average horse could gallop at, but the car could do that speed for much longer periods of time.

1899 would be a difficult year for Daimler. Personally his age and health problems were advancing, at DMG the subversive acts of Max von Duttenhofer would bring the firm great problems. The rate of technical development by Maybach continued and expanded when DMG engines powered Count Zeppelin's new LZ1 airship when it made its maiden flight in February 1899.

The older Riemenwagen was discontinued as the 6hp, 4-cylinder engined Phoenix-Wagen became so popular. Not surprising with the thrill of a top speed of up 40kph available to the driver. But despite the sales of this vehicle DMG dropped out of the black and was unprofitable. The reason was Max von Duttenhofer and Kilian Steiner.

The grudges they still held led to some underhanded dealings that played into the hands of the competition. In short, Duttenhofer created false documents that allowed Daimler engines and parts to be built by other firms, who then undercut the DMG prices and slashed DMG's profits as sales fell away.

By the time Daimler realized what Duttenhofer and Killian had done it was too late. Gottlieb tried to negotiate with them and prove the patent rights given by Duttenhofer were not real but all proved fruitless. The whole affair took its toll on his health and his heart condition flared up again.

With financial issues besetting the firm Daimler was once again forced to look externally for financing. Fortunately a loyal customer, Emile Jellinek, who bought his first Daimler in 1896 and had bought more in the following years, becoming a Daimler agent selling the firms cars in France and beating the delivery times of P&L and Peugeot, stepped in with a plan to put money into the firm.

Jellinek, by this time well known to Daimler and Maybach was not the best liked customer. He had a habit of making suggestions on the design front which annoyed Daimler. However, Jellinek did read and study the designs of motor cars which prompted Maybach to follow some of his ideas.

Emile Jellinek, a wealthy diplomat, motoring enthusiast and Daimler owner/race driver joined the Daimler Board of Directors and encouraged them to start building high performance "sports" cars. To get DMG to agree, Jellinek had to agree to place an order for 36 cars, but if he was to be spending so much money Emile Jellinek insists on a change of brand name! ‘Mercedes’, the name of his eldest daughter, was to be the brand name for the new sports cars.

Then, Jellinek insisted on having the Trade Rights throughout the Austro-Hungarian Empire, France, Belgium, and USA, and to trade the cars as ‘Mercedes’ in these areas. pretty shrewd!

Wilhelm Maybach was put in charge of the “Mercedes” project in 1900 and followed Jellinek's broad specifications. Daimler himself was ordered to stay away from work due to the effects on his health and spent most of the last months of his life in bed. Apparently he had been caught in very poor weather during a trip late in 1899 which had further exacerbated his ill health.

Sadly, Daimler didn't live long enough to see a Mercedes sport-car. For DMG the Mercedes proved to be very popular and oversold Jellineks pre-purchased order for 36 cars by so many it had to be put into production.

Gottlieb Wilhelm Daimler passed away in his home in Cannstatt, Stuttgart, on the 6th of March, 1900, his failing heart finally giving out at the age of 65. A lifetime at the forefront of automotive engine technology; over. Daimler was lain to rest in the Uff-Kirchhof cemetery, Stadtkreis Stuttgart, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

An obituary by Edwin Emerson Jr. in the Automobile Magazine hailed Gottlieb Daimler as “The father of the automobile”, and “a guiding spirit” who “revolutionized the construction and industry of light mechanical motors.”

Daimler was inducted into the Dearborn, Automotive Hall of Fame, in 1978 and into the Geneva, the European Automotive Hall of Fame, in 2001. The football stadium in Stuttgart was named for after Gottlieb Daimler between 1993 and 2008. A FIFA World Cup venue in 2006, the stadium had now been renamed “Mercedes-Benz Stadium”. A clear case of money through sponsorship trumping actual homage to an historic local inventor.

A more touching memorial is the commemorative plaque unveiled in Daimler's honour in June 1902 by the Association of German Engineers (VDI). The plaque is set into a rock near the Daimler garden house in Cannstatt. The house itself being a museum of the man and his pioneering work with Maybach.

The Schorndorf home, in which Gottlieb Daimler was born, was purchased by Daimler-Benz AG in 1979. It was painstakingly renovated and restored to the layout of the now world-famous bakery and wine bar at the time of Gottlieb's childhood. No expense was spared in doing so either. Today it houses models and exhibitions of documents etc. that cover the life and work of Daimler. A guide in period dress depicting Gottlieb's wife, leads visitors through the house explaining the life and times of the late nineteenth century Daimler's.

Legacy

The turn of the 20th century showed an upturn in DMG fortunes from the "Mercedes" project. Wilhelm Maybach left DMG in 1907 to work on projects for the Zeppelin airships, eventually setting up his own factory for that purpose. With his leaving DMG the start of a new era began, or at least a finishing of the foundations if you will.

Becoming Daimler-Benz AG in 1926 then Mercedes Benz Automobile Company later, the firm Gottlieb Daimler co-founded is still one of the world's top luxury and sports car brands, as both as Mercedes, and Maybach. Not to mention the Mercedes racing heritage upheld in Formula one with numerous drivers and constructors championships.

While Shorndorf is still sometimes called “Die Daimlerstadt”, or the Daimler City in English, it is only the automotive faithfull who remember it and the man whose life and inventions created so much of the pioneering work in the modes of transport we take for granted today. The world has moved on, 125 years after Gottlieb Daimler's death.

Gottlieb Daimler was a workaholic. Renowned for his drive and precision he lived his personal motto of "Das Beste oder nichts," meaning the best or nothing at all; a motto adopted by Mercedes-Benz as the company slogan in 2010. Appropriately, as Daimler was a man who prided himself on precision, and as a boss insisted on quality standards and who "instituted a system of inspections". Gottlibe was a perfectionist who drove himself mercilessly; and often those who worked around him too.

Engineer, industrial designer, visionary genius and automotive pioneer Damiler's occupational title of “Maschinenbau Konstruteur und Automobilerfinder” (Mechanical engineering Constructor and automotive inventor), fails to adequately describe the great man's varied practical experience and ability to develop ideas and designs into something more than they were.

Daimler's legendary collaboration with his close friend Wilhelm Maybach created so many inventions improvements and patents, that it is had to untangle which of them did what within their symbiotic drive to create their small, high speed engines that could be used to propel machines on the land, on water and in the air.

Once the pair had their engines they moved on to pioneer the automobiles themselves, some fifteen individual vehicle designs. Motor cars, trucks and buses were all built by Daimler and Maybach prior to 1899.