Rome's gift to Britain

Roman roads were a vital part of the development of the Roman state. Roads allowed the state to communicate quickly, move armies and trade goods. Throughout the expansion of Rome from around 500 BC through the Roman Republic and on into the Roman Empire, roads played a keen part in securing and funding the Roman state. At it's height the Roman road system consisted of over 250,000 miles of roads, of that, over 50,000 miles were paved roads.

When Rome reached the height of its power, no fewer than 29 great military highways radiated out from the city. Hills were cut through and deep ravines filled in. When the Roman Empire was divided into 113 provinces it could be traversed by 372 great road links. 13,000 miles of road were said to have been improved in Gaul, and at least 250 miles in Britain; roads that also had footpaths on each side of the road.

Romans became particularly adept at constructing roads, or to use the Latin term viae. Intended for carrying material from one location to another it was permitted to walk or pass and drive cattle, vehicles, or traffic of any description along the path. The viae differed from the many other smaller or rougher roads, bridle-paths, drifts, and tracks.

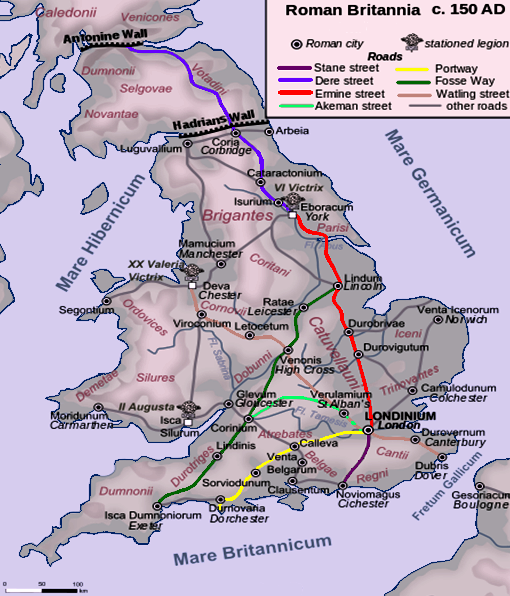

The old Roman proverb that "all roads lead to Rome" was largely applicable in Roman Britain, or Britannia, too.

During the 2nd century Londinium was at its height and replaced Colchester as the capital of Roman Britain, as a result the most important trunk roads were those that linked London with the key ports of Dover (Dubris), Chichester (Noviomagus) and Portchester (Portus Adurni); and the main bases of the Roman army which were the three permanent fortresses at York (Eboracum), Chester (Deva) and Caerlon (Isca Augustus).

From Chester and York, two key roads led to Hadrians Wall, for most of the period Britannia 's northern border, where most of the three legions' auxiliary units were deployed.

From London, six core routes radiated. Ignoring their later Anglo Saxon nomenclature they are as follows :-

1, London - Dover via Canterbury (Durovernum)

2. London - Chichester

3. London - Silchester (Calleva Atrebatum, near Reading).

At Silchester, this route split into 3 major branches:

i. Silchester - Portchester via Winchester (Venta Belgarum) and Southampton (Clausentum)

ii. Silchester - Exeter (Isca Dumnoniorum) via Salisbury/Old Sarum (Sorviodunum) and Dorchester (Durnovaria)

iii. Silchester - Caerleon via Gloucester (Glevum)

4. London - Chester via St.Albans (Verulamium), Lichfield (Letocetum), Wroxeter (Viroconium), with continuation to Carlisle (Luguvalium) on Hadrian's Wall

5. London - York via Lincoln (Lindum), with continuation to Corbridge (Coria) on Hadrian's Wall

6. London - Caister St.Edmunds (Venta Icenorum) via Colchester (Camulodunum)

This road network, built by Roman Soldiers, was set up to facilitate military communications, it linked up army bases rather than catered for local needs or the economics of trade. As the frontier of the Roman-occupied zone advanced three important cross-routes were established early by 80 AD :-

Exeter - Lincoln (Fosse Way), Gloucester - York (Icknield Street) and Caerleon - York via Wroxeter and Chester.

Later a large number of other cross-routes and branches were grafted onto this basic network.

Unlike their counterparts in Italy and some of the Roman provinces, the original names of Roman roads in Britain are not known due to a lack of written and inscribed evidence. Instead, there are a number of names ascribed to them by the Anglo-Saxons during the post-Roman era.

The English classification of a particular road does not correspond to the likely original Roman name e.g. the Anglo-Saxons gave the name Watling Street to the entire route from Dover to Wroxeter, via London. But the Romans may well have regarded the first section - Dover to London - as a separate road with a different name from the second section - London to Wroxeter.

The only Anglo-Saxon name which may echo an original Roman name is the Fosse Way - Exeter to Lincoln. Even then it is likely to derive from a popular, rather than official, Roman name for the road. "Fosse" may derive from the Latin fossa, meaning "ditch"

The Romans had many years of knowledge and skills at their disposal. Their infrastructure of roads, bridges and towns had given the ruling military power security and access to all the important areas of the province. This meant trade for the Romans, and for those who chose to adopt their way of life, was enhanced.

For other locals this infrastructure did little so when the Anglo-Saxons affirmed their power, after the Romans left, they abandoned many of the Roman roads, failed to maintain the ones they did use and built their own new roads. The Anglo-Saxons were not at all as successful as Romans in this area of endeavour; it has been said that the Romans built roads with their hands, but the Anglo-Saxons built roads with their feet.

Many of the roads were little more than dirt tracks, sometimes grassy, often muddy. Formed only by the repetitive use of the local people. For carts, and even travellers on foot, this presented nothing more than a difficult journey; and it was to be that way for around a thousand years.

RETURN TO :-