1956 Lotus Eleven

Colin Chapman was a rather reluctant employee of the British Aluminium Company Ltd, but spent his spare time he designed and built special, lightweight sports cars. He was an avid reader and would read every piece of information, however small, on the particular subject that had his attention at the time. His car designs started with so called “Specials”, based on Austin Sevens, for trials and hill climb competitions. He was so inundated with requests from other competitors to them a copy that he started doing so. This led to requests from circuit racers and Colin's interest in club racing grew rapidly.

Starting a small business, which he worked on in the evenings, Chapman started putting his designs into production. The mark VI was first car Lotus put on sale, it was in sold in kit form and introduced the term "space frame" to British buyers. Working out of a small premises in Hornsey, North London, Chapman slowly built up his reputation for entirely functional, nimble and amazingly efficient cars which were also a little fragile.

The MkVI was a good car in its mechanical aspect but it had the aerodynamic qualities of a brick. One of the part time employees, Mike Costin, had a brother who was working for De Havilland Aircraft co. as an aerodynamicist and Chapman sweat-talked Frank Costin into consulting on the bodywork designs. Costin treated the MkVI as a ideological challenge and developed the MkVI panels into a more elegant car. Following Lotus cars had ever more attractive, efficient and unique bodies which, mated to Chapman's intuitive mechanics produced almost unbeatable racing cars.

The Lotus Eleven, launched early in 1956, was an amazingly advanced design. The rigid spaceframe chassis had stressed skin panels bonded to it and the enveloping bodywork was not only beautiful but incredibly functional. Chapman was well known for his philosophy that each part should do two jobs at the same time and have no more mass than needed to do the job. This formed the basis of Lotus' reputation for 'scientifically designed', but fragile, cars.

Costin's work on the body went along with this idea. The the aerodynamic body (tested by the magazine “Road & Track” who calculated it needed just 9hp to push it along at 60 mph), not only aided in stiffening the tubular space frame but also hinged at both ends giving the mechanics quick and complete access. The use of a spaceframe chassis wasn't exactly novel, as it was originally used in aircraft design. Jaguar's 1951 for the “C” type and Mercedes 1952 300sl both also used a spaceframe chassis. But it took Chapman to design a chassis weighing just 56lbs, even with the stressed skin on it stayed under 70lbs. He hit the sweet spot both aerodynamically and in power to weight ratio terms too. The engine was usually a 1,100cc Climax FWA engine it had an impressive power-to-weight-ratio in the region of 204 bhp per ton.

The Eleven had tenacious grip from a front suspension modified from very humble Ford “Popular” parts and a live rear axle with de Dion tube location. The cheaper “club” version had an Austin live rear axle and drum brakes all around, Girling disc brakes were the norm on the “Le Mans” spec cars. 1957 Series two cars had more forgiving and consistent front end courtesy of double A-arms, Lotus 12 style.

Always quick and agile the Lotus Eleven was available in a range of versions with several different engine options. The le Mans and Club versions had 1100cc Climax engines the le Mans had the 1500cc Climax option too. The Sport used a 1172 cc Ford engine. This three model option was an important step for Lotus as Chapman wanted the car to sell not only for the different areas of club circuit racing but for public use on the roads; increasing sales and thus better funding for the racing car designs.

It was also important in another way too as it marked the start of the Lotus tradition of naming cars starting with the letters “El” (Elan, Elise etc), and latter simply starting with E (Esprit, Eclat).

The obsessive nature of both Chapman and Costin made the Lotus Eleven (which should also be written in letters not numbers), the technical pinnacle of automotive design. No compromises, no shortcuts.

Such was the

combined effect of good horsepower, low weight, unmatched

aerodynamics, powerful brakes and exemplary road-holding, that rival

designers were at once dismayed and astounded. As car followers they

couldn't help but admire the lines of the car; as competitors they

were stunned by the performance and at a loss for how to match it.

Unreliability was the one factor that might come into play. Poorly

maintained or excessively over driven Elevens did show signs of

stress failures in the chassis and component breakages, Chapman

himself always seemed remarkable undisturbed by criticism of

fragility levelled at the Lotus.

The race drivers of the day

saw the eleven as THE car for winning races, amateur racing

enthusiasts rushed to order the new Eleven and the bookies soon saw

the Eleven as favourite to win almost any race they were entered in.

It wasn't long before the cars results were backing up those ideas.

In the 1956 season the Elevens scored at least 148 race wins. At the 1956 24 hours of Le Mans the quick and agile Eleven proved it could also last the distance. Reg Bicknell & Peter Jopp drove their Eleven to finish seventh overall and win the 1100cc sports car class.

They went even

better in 1957 with new wrap around windshield cars, the American

crew of Mackay-Fraser and Chamberlain recording an average speed of

99.08 mph on their way to 8th overall. In fact all four team cars

finished. Walshaw & Dalton finished 13th, Hall & Allison were

14th & 1st in 750cc sports class, (and averaged 90 mph to win

index of performance) while Masson & André Héchard finished

16th overall.

Also a specially streamlined Eleven, modified by

Costin to have a bubble canopy over the cockpit, was driven by

Stirling Moss, and at different times "Mac" Fraser, to set

a series of closed track world speed records at Monza. The 1,100cc

car covered 100km at 135mph with a fastest lap of 143 mph (230km/h).

For the seasons from 1956 to 1958 the Eleven reigned supreme in its class and even in 1959 it could still hold it's own. Later some of the cars were fitted with a closed body and gullwing doors to race in GT specifications.

It is fair to say this tiny, front-engined sports car with two seats (and a very minimal level of weather protection) was an instant success. Chapman, a peerless self-publicist, was soon claiming that Lotus was building this car at a rate of four cars every week. For sure Chapman's neighbours Progress Chassis Co. and Williams & Pritchard were turning out chassis and body panels at a fair rate as sales of built cars and kits grew rapidly. It is believed, including all versions, that around 270 Elevens were built or sold as kits. These numbers mark the Eleven as Lotus' most successful race car design and firmly established Lotus as serious competition car makers.

If the sincerest form of flattery is imitation then the Eleven is a roaring success as the Kokopelli 11, the Challenger GTS, the Spartak and the best known Westfield XI are all Lotus Eleven replicas or re-creations.

1/24th scale kit.

Built by Ian.

DEC 494 chassis #173 and #211

Two Lotus Eleven chassis have carried the registration number DEC 494 and their stories are linked by more than just being Lotus Elevens.

Chassis # 173 was built early in 1956 and was soon racing, entered regularly by Team Lotus. More often than not the car was driven by a new driver Chapman himself had spotted, Cliff Allison. During his 1956 season, which ran from 2nd of April to 21st of October 1956, Allison took 4 wins in the car always entered by Team lotus.

But the car was driven by others too, including Graham Hill for one, and it is one of Hill's drives we have chosen to replicate with our model.

On 29th of April 1956 Graham Hill drove this car to 1st place in the 12 lap Brands Hatch National sports (1.2L class) car race, his winning speed being 69.750kph. On the same day Hill also drove the car in the sports (1.5L class) car race and finished 2nd to Reg Bicknell's larger engined Lotus11.

The second chassis, chassis #211, linked by the registration number was also a Cliff Allison driven car and Allison would have his own part to play in further linking the two chassis.

Lotus Eleven, model nomenclature 11/model S1 LMW, chassis #211 was built in July 1956 as one of a special group of Elevens built especially for racing in the Grand Prix d'Endurance that is the 24 heures du Mans on the 28-29th July 1956. This chassis was driven by Cliff Allison and Keith Hall carrying the race number '35' while two other Lotus team cars were also entered, Colin Chapman himself driving one with Herbert Mackay-Frazer.

There are some stories around this car and the race that stand out in history for quite different reasons. Firstly the registration number 'DEC 494' belonged to the Cliff Allison Lotus Eleven, chassis #173. As Le Mans regulations require the cars to have a road registration number to compete Allison suggested "you can use the number of my car, nobody will know", Of course historically we do know and that the same registration number was used by Lotus in other races to!

As for the '56 Le Mans race the Allison/Hall car was on its 90th lap when very large Alsatian dog suddenly appeared out of the misty night on the Mulsanne Straight. Cliff moved right to avoid the dog just as it changed it's mind and turned round to move right too!

Colin Chapman's car, carrying number '32', ran for 172 laps before its engine failed.

This car later carried the same registration number when Ian Smith and Tim Martin drove the car for a trial from Lands end to John O'Groats which resulted in an average speed for the 892 miles of 51.06 mph. The duo had to travel back to Wick to fill up the fuel tank and found that, having used 23.75 gallons for the extended distance of 915 miles, the Lotus Eleven had given an average fuel mileage of 38.525 mpg. These figures proved to the motoring public that the Lotus Eleven was a viable road going car as well as a racing car.

The Merit Kit

The Merit kit of the Lotus Eleven was amongst the several contemporary racing car kits issued in the late 1950s and early '60s, most of which feature somewhere in our museum website. J & L Randall Ltd was a British toy manufacturer from Potters Bar, Hertfordshire. Merit was the company's brand for general plastic toys and it's plastic model kit range flourished in the 1950s and 1960s. Merit kits of aeroplanes and ships were also available and the company was heavily into plastic railway accessories. But the the racing cars range is now considered classic and highly sought after today. The range consisted of 14 cars from the 1940s and '50s, two of them (the Alfa 158 and the Talbot-Lago), were sold as 'superkits' and had engine detail.

A French company called Sitaplex also released some of the Merit road and race cars in the 1960s. They were a contract moulding company and also released some Heller kits. Mostly remembered for ship and aircraft kits we know the company did release several of the race and road cars, the race cars in boxes similar to the Merit ones and the road cars in Airfix style bags and a red header quite different to the Merit sales material.

These are the ones we know of for certain though there are sure to be others. Lotus Eleven - Ferrari D50 - Rolls-Royce limo.

Merit Lotus Eleven restoration build

Bought off ebay in 2015 this model was previously built (hence the before and after photo's) and had obviously been neglected for a long time. One wheel was completely missing, other parts were broken and the whole thing was very dirty. BUT; as these models come up for sale at affordable prices so rarely, as the collectors prices are just too high for a builder to justify, Ian had to take the chance while he could. Of course Ian and Rod have the necessary years of experience to take a built model and restore it to an as new condition.

The kit has been seriously updated by Ian. The cockpit has been detailed with chassis and control details like the gear shift lever, detailed steering wheel and dashboard, and much more in the cockpit area, even the fuel filler, visible externally, links through properly to the tank inside. The chassis is also detailed by the addition of internal structures to block light showing through and a proper radiator in the front of the chassis.

Wanting to make the model more realistic and up to date the Merit body was cut back into the panels as on the real car. Merit's kit is a simple two part upper and lower halves system familiar to older modellers but seldom used these days on high level kits. Cutting and shaping the panels also means a certain amount of plastic loss during the cutting which had to be replaced during the building, as in the during photo's. To add to this effort for realism Ian removed the raised panel lines and scribed in recessed ones, except for the tonneau cover which sits on top of the car body and has a rolled lip edge.

Externally the kit has scratch built fasteners and added rivet detail, as well as the addition of the main body underneath the add on headrest and wrap around cockpit. A new windscreen was fashioned from clear plastic after the original was broken. The technique is to put masking tape over the kit screen, cut it to size then transfer the tape to a clear piece of plastic sheet. This in turn is cut and size and shape before being put in the placed on the model. Other external details needing attention were the door hinges, the amended rear end detailing, the light openings and all the front lights themselves as well as the light covers; even the rear view mirror had to be sourced elsewhere.

One of the things that seriously lets down the old Merit kits is the clear disc and spoke decal system. Great in the late '50s, superseded several times over since then. The best current system is photo etched spokes. Given that the kit had a wheel missing anyway Ian had little choice than to go looking for replacement wheels. The set used are from South Eastern Finecast and were discovered by chance at the 2015 IPMS Scale Model World show by a friend who knew I was looking for something like these (Thanks Alex). They aren't exactly right but they are close and look the part especially given that the wheels are largely covered anyway.

In the end all the work is worth the effort but it takes time and dedication with not a little frustration at times! The way round the frustration is to keep lists of jobs to do and put the model aside when it is too taxing and go away and do a different model. This reduces the chances of getting too upset and throwing the model away while keeping you on track when you return to the build.

In the end what was 20 to 30 part kit turned into a model with so many individual parts Ian lost count of them. The model is painted by airbrush for all the priming (alclad II primer) and main painting. The body colour was mixed to match photo's using Deco-Art acrylic paints. The gloss coat is Plamo standard gloss. Detail painting and washes applied by brush used Citadel acrylics and Humbrol enamels.

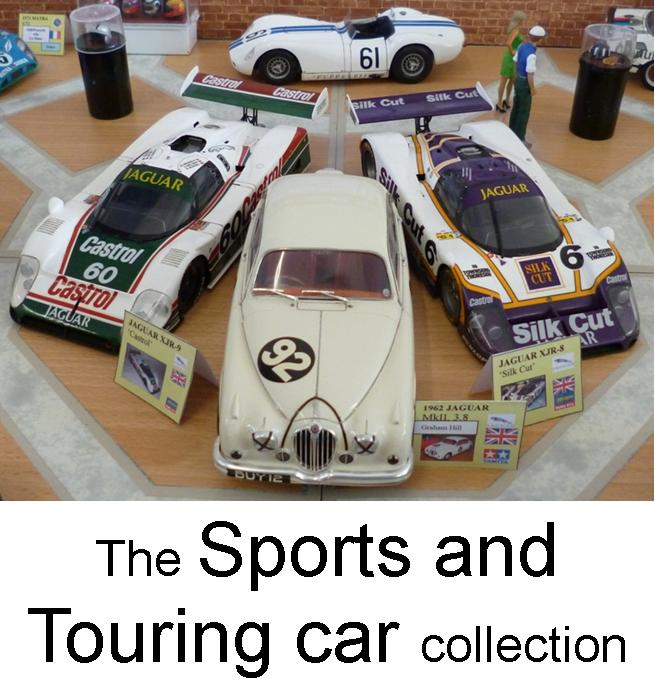

RETURN TO :-